by Gennady Shkliarevsky

The war in Ukraine gives rise to many hypothetical speculations of the “what if” type. One such speculation has recently gained much attention both in Ukraine and in the West. It concerns relates to what many think was a fateful decision made back in 1994 that led to Ukraine giving up the nuclear arsenal that the country inherited after the break up of the Soviet Union.

In his speech in the Ukrainian parliament, for example, David Arahamia, the head of the parliamentary faction of Zelensky’s Servant of the People party, accused Leonid Kravchuk, a former president of Ukraine who is now deceased and who was a party to this decision, of betraying Ukraine by agreeing to give up nuclear weapons. “I think,” he stated, “he has made a fatal mistake by getting rid of nuclear weapons after he signed the meaningless (Budapest) memorandum. We are now paying the price for this enormous mistake.”

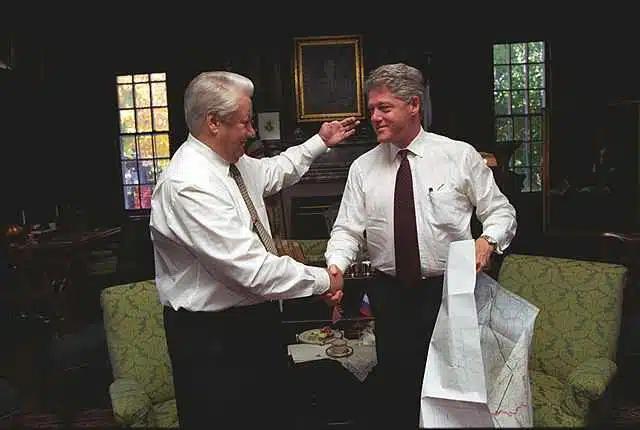

Among those who have spoken recently about this decision is Bill Clinton, who, as American president, was also a party who signed up to the Budapest Memorandum back in 1994. Clinton has also become a target of criticism in Ukraine. Ukrainians blame him for the country’s current woes. Answering his critics, Clinton has recently made statements in the media that amount to his “moment of truth.”

Candor and honesty are not qualities that we associate with Clinton. He lied frequently and brazenly throughout his political career, both before and during his presidency. We all remember his famous “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, with Miss Lewinsky,” that he said, looking straight into the camera to millions of Americans. Having a “moment of truth” for Clinton is not common, and yet here he is with his declaration of mea culpa to the whole world. But Bill Clinton would not be Bill Clinton if, even in his “moment of truth,” he did not try to pull a fast one on his audience.

The occasion was an interview that Clinton gave to an Irish broadcaster on RTÊ’s “Prime Time” last Tuesday. In this interview, Clinton confessed that he felt guilty because he “got them [Ukrainians] to agree to give up their nuclear weapons.” He also admitted that Putin would not “pull this stunt” if Ukraine now had a nuclear arsenal; he would not have dared to invade Ukraine in 2014 and would not have annexed large swaths of Ukrainian territory.

Clinton’s interview creates an impression that the idea of removing nuclear weapons from Ukraine belonged primarily to Yeltsin (Russian president at the time who is now also deceased) who “wanted Ukraine to give up their nuclear weapons.” He credits himself with a foresight of knowing that Putin, who was a minor figure hardly worthy of attention back in 1994, “did not support the agreement” to ensure Ukraine’s independence.

“When it became convenient to him,” Clinton explains, “President Putin broke it [the agreement] and first took Crimea, and I feel terrible about it, because Ukraine is a very important country.” Clinton also added: “I think what Mr. Putin did was very wrong,” and he should pay the price for violating the trust put in the agreement. Clinton urged the United States and the West to continue their support for embattled Ukraine: “I don’t think the rest of us should cut and run on them.”

In his comments to Prime Time on Clinton’s interview, Larry Donnelly, a law faculty at the University of Galway, expressed his admiration for Clinton’s candor that he certainly wanted his readers to share. Unlike Ukrainians, Donnelly did not chastise Clinton for his role in the decision.

“It is understandable,” he argued, “why he [Clinton] did what he did,” thus clearly conveying his conviction that there was really no other way to act in that situation. Donnelly attributed to Clinton idealistic motivations in trying to denuclearize the world, improve relations, and engage Russia constructively.

In Donnelly’s depiction, Clinton emerges as a tragic figure caught in circumstances beyond his control. Clinton also comes up as a heroic figure suffering for something that is not really his fault. Yet Donnelly understands his regrets, as well as the anger of the people in Ukraine. His hope is that Clinton’s confession will move people in the United States and in Europe on a moral level to continue the support for Ukraine—the country that has become a victim of international politics and a vile dictator in Moscow.

The narrative that Clinton and Donnelly create does not tell the whole truth. In fact, it omits and is silent about some very important pieces of evidence related to the early 1990s contained in many interviews and publications, including those by Leonid Kravchuk who was the president of Ukraine at the time.

This evidence shows, for example, that the initiative in depriving Ukraine of nuclear weapons really belonged to Clinton and the United States, not Yeltsin and Russia. In several statements, Kravchuk made clear that the demand to give up nuclear weapons and missiles was dictated by the White House, not the Kremlin.

Kravchuk is somewhat unclear as to why Clinton insisted on his demand. In one piece, he intimates that the reason was most likely fear since many missiles in Ukraine were targeted on the United States. Clinton and his administration wanted to remove them so as to diminish the threat to America.

One wonders, though, if this approach was the only one possible that could address American concerns. After all, targets can be changed. On other occasions and in his book The Test by Power, Kravchuk also cited another reason. He said that the missiles and warheads were old and posed a danger to Ukraine, and that is why he agreed to remove them.

Be that as it may, one thing is clear, the initiative to remove nuclear weapons from Ukraine came from the United States, not Russia. In 1994 Russia was too weak and not in a position to make demands on anyone. The United States, on the other hand, was at the peak of its power following the collapse and the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

The evidence provided by Kravchuk also shows that Ukraine was not rushing to get rid of its nuclear weapons and had some second thoughts about the move. However, Clinton and his administration were relentless. They ignored all reservations and concerns expressed by the government of Ukraine and insisted on their demands. They also resorted to some heavy-handed tactics to get their way.

Washington began to threaten Ukraine with isolation and even a full-scale blockade in case of insubordination. In Kravchuk’s own words, the Clinton administration “gave us a choice: either we remove nuclear weapons, or they will apply economic pressure, including sanctions,” including sanctions—something that Ukraine could not really afford at the time. “If you refuse to implement our demand,” Kravchuk quoted the American side, “and will not remove nuclear warheads, our response will not be mere pressure; we will blockade Ukraine.”

The evidence tells a full story about the way America treated Ukraine in this episode; and it is very different from the one that Clinton and Donnelly try to create in his narrative. Washington, not Russia, was the principal player that made demands on Ukraine and thus violated the country’s sovereignty in making the decision that was to become fateful.

It is difficult to believe that Washington felt really threatened by missile located half a world away from America in a country that could not pose a threat to anyone at the time. It is also difficult to accept the explanation that the Clinton administration had environmental concerns caused by the aging warheads and missiles. Kravchuk reported that the United States did not provide nearly enough money to eliminate the environmental danger presented by the nuclear weapons.

According to Kravchuk, he personally and repeatedly explained to Bill Clinton and Al Gore that the decontamination of each silo in Ukraine should cost about a billion dollars and that Ukraine had them several hundreds of them. Western estimates at the time were that Ukraine needed $200 billion to prevent environmental contamination. Yet Ukraine received a mere $950 million from the American government–hardly enough to even make a dent hardly enough to even make a dent.

So, if it was not a possibility of an imminent nuclear threat and or t a concern for the environment, what could then be the reason why the Clinton administration wanted Ukraine to give up nuclear weapons?

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States emerged as the only country in the whole world capable of global control. There was a clear sense of triumphalism in the air. Francis Fukuyama captured this spirit in his now famous book The End of History and the Last Man. Fukuyama and many others believed that there was a real chance to end all conflicts and create an eternal peace with the United States as its guarantor.

But the men in Washington were no mere dreamers and idealists. They were practical people, and they sought practical ways to realize this vision. They decided to use the American military might as the main tool for realizing this grandiose project. The results are well known now. The quest for eternal peace led to several wars conducted by American presidents to bring about the new world order and the unprecedented expansion of NATO that had originally had the purpose of defending Europe against Soviet communism but now has acquired a global significance and reach in the minds of American planners.

In the minds of American neo-liberals and globalists, Russia was supposed to break up into pieces that would obediently fall into the orbit of American supremacy. These plans for Russia have miserably failed. Russia has rebuilt itself and re-emerged as a credible power in the region. As a regional power, Russia also seeks peace and security. After all, Russia has experienced in the past two major invasions by European powers—one under Napoleon in 1812 and another under Hitler in 1941. Russia paid a huge price in both these invasions, particularly one led by the Nazis (it lost over twenty million people in the war of 1941-1945). Russia is now determined to ensure its security and integrity.

In its search for security, Russia has repeatedly asked the United States to limit the expansion of NATO. Russia gave up its Warsaw Pact to assure the United States and the West of its intention to live in peace. Yet their repeated demands and assurances fell on deaf ears. In its quest for world domination the United States was determined to continue its forward march.

The country that seeks absolute domination puts itself in a very precarious position. It is always destined to feel insecure since it always feels insecure in its aspiration. The expansion has continued and now extends to directly to countries that Russia legitimately feels to be its security zone.

When reviewing the events of nearly thirty years ago, one cannot resist the temptation to view these events through to lens of the current war in Ukraine. Was the plan to deprive Ukraine of nuclear weapons and make it vulnerable really a ploy to make it eventually part of NATO, expand the large territory enormously now under NATO control, and put the country’s enormous human and natural resources at the disposal of the United States and NATO, but most importantly, to make Ukraine the bridgehead for the future expansion of NATO? How far?

What could be the next country in the Russia security zone that would become the object of expansion? Georgia? Kazakhstan? Some Central Asian states? Only the planners in Washington can answer these questions.

Who can say that the plans for such expansions do not really exist already in some vault in Washington? Will they really resist the temptation to be the rulers of the world? I doubt it. Their goal appears to be very noble: to bring eternal peace and security to the whole world. But is there anything that paves the road to hell with greater certainty than noble intentions?

~~~

Gennady Shkliarevsky is Professor Emeritus of History: Historical Studies Area of Specialization: Russian and Soviet history Biography: BA, MA, Kiev State University; MA, PhD, University of Virginia.

hmmm thought that BiLewensky was suicided already.

For a period of about 15 years Ukrainian oligarchs were the leading donators to the Clinton Foundation. Ukraine is the world’s corruption playground for connected people and politicians. This is why they are fighting so save it.

The Clinton’s are liars? Who would have thought!