A senior Federal Reserve official said Monday that the U.S. central bank is prepared to step in with emergency rate cuts if the economy sinks. The Feds think the markets are overreacting if you can believe them.

Austan Goolsbee, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, told CNBC’s “Squawk Box” on Aug. 5 that as inflation has come down, the effective federal funds rate is as high as it has been in a long time. He suggests the policy might be too restrictive.

“We’ve been in a restrictive posture at the Fed,” Goolsbee said. “And you only want to be that restrictive if you think there’s fear of overheating. And that these data, to me, do not look like overheating.”

Maybe but I don’t trust Goolsbee. I don’t trust Keynesian economists.

Data emerged last week showing deterioration in the U.S. labor market and manufacturing, including an 11-month high in initial jobless filings, a manufacturing gauge sinking deeper into recession territory, job creation numbers that came in well-below expectations, and an unemployment rate that jumped higher than anticipated.

In Case The Economy Tanks

Goolsbee said the Feds are always ready to step in for an emergency. He said the Fed’s mandate is “straightforward”: to stabilize prices and maximize employment.

“And that’s what we’re going to do,” he said, while not committing to any particular course of action, noting that the jobs numbers have come in weaker than expected, but “not looking, yet, like recession.”

Their definition of recession is ever-changing.

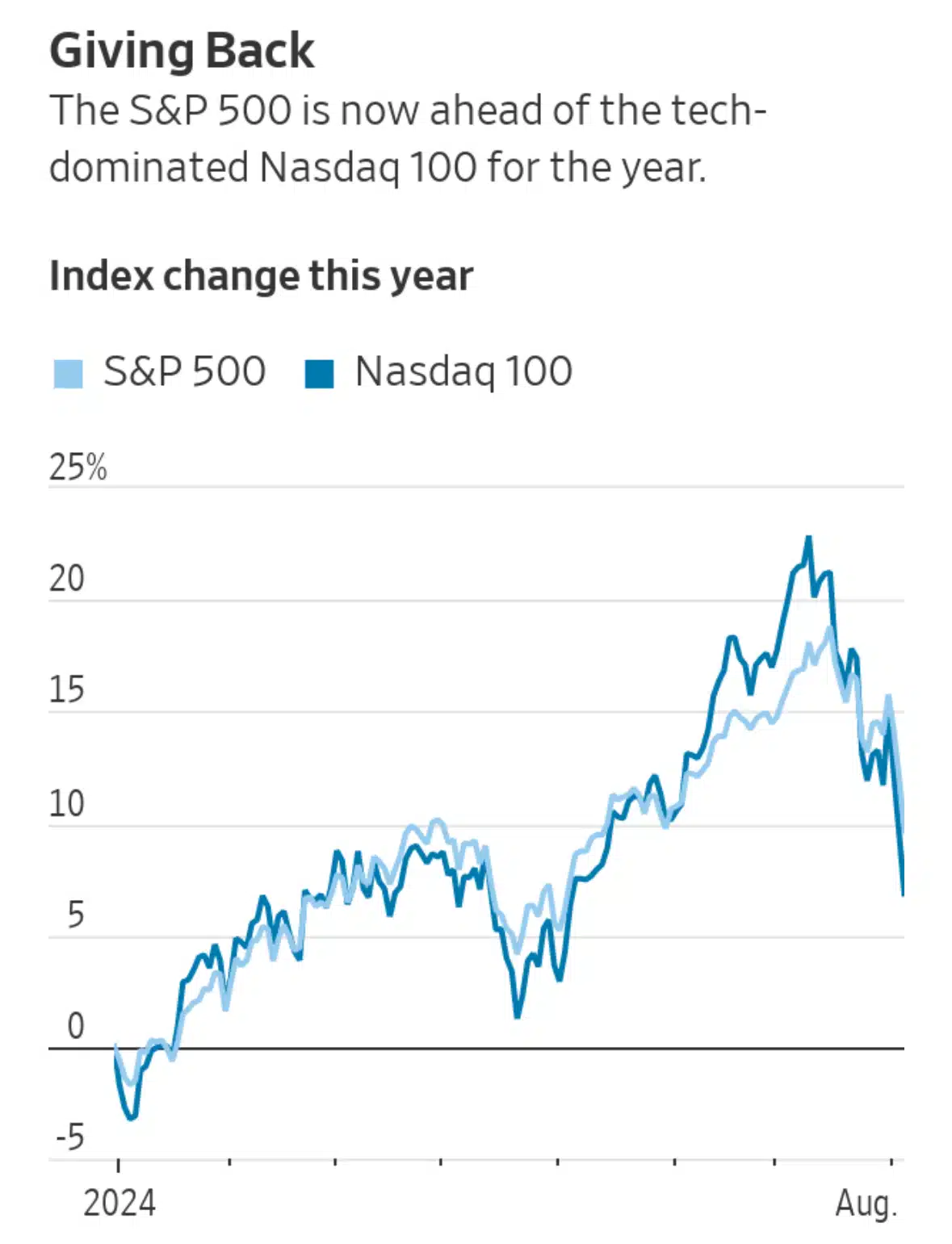

The Wall Street Journal Sees an Overreaction

The Wall Street Journal said Friday’s job report was “the trigger for the markets sell off, but the triggers can’t possibly justify the scale of the moves. The selloff—which at one point had chip maker Nvidia down 15%—was big because investors had been all-in betting that things would work out well. The question is how far the unwind of these bets—and the leverage behind them—will go. If it continues, will the selloff feed back into higher savings and a weaker economy or, worse, hit the financial system?

“The extreme examples of past effects from big market falls are 1987’s crash, 1998’s Long-Term Capital Management blowup and 2008’s global financial crisis. History is never perfect, but so far this looks more like a (milder) version of 1987 than it does the other two.”

In the end, it’s a big betting parlor and no one really knows how it will turn out.

Has anyone noticed that weeks ago Warren Buffet and bug tech CEOs have sold off billions in their stock portfolio?

The problem (the fed) will help the situation?

How about we just eliminate the central bank and quit allowing Wall Street to dictate American financial policy? Novel idea, I know.

I shorted the S&P index last week. I’m making a killing today. Positions closed now, waiting for next opportunity. F the FED!

If putting your finger in the dike after dam is broke is helping, yea they helped. Welcome to a brand new soft crash, oop’s forgot to extend the land gear.

If the economy tanks? Whut? Look around you. The FEDS are part of the tanking, jeez we’ve become a nation of idiocracy!