Updated May 29, 2019

The most deranged decision the Court has made, since Dred Scott in 1857, was Roe v Wade in 1973, when the Supreme Court fabricated constitutional protection to women seeking an abortion. Both decisions denied the “personhood” of two unmistakably human entities, and declared them to be merely property.

Now, it seems the SCOTUS intends to correct the glaring error in Roe —that unborn children are less than human.

Yesterday, the Court ruled that state laws mandating fetal parts must be buried or cremated [like humans!] are constitutional.

The Court, which was ruling on an Indiana law, did not rule on a provision that banned abortions based on race, sex or disability of the fetus. The key point is disability, which includes Down Syndrome. The 7th Circuit struck down that provision, meaning the state couldn’t enforce that part of the law.

However, the High Court was simply following its practice of not ruling on the merits of that provision until an appeals court had heard the case. After that happens, we may see the Court upholding Indiana’s power to ban abortions based upon disabilities of the fetus.

in Roe, the High Court created a fictional right to privacy that was hitherto undiscovered in the Fouteenth Amendment:

This right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or,… in the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.

Ironically, the Fourteenth may be used to achieve the unraveling of Roe.

-

The Importance of Prayer: How a Christian Gold Company Stands Out by Defending Americans’ Retirement

Establishing the personhood of the unborn reverses Roe

Citing the Fourteenth as justification for killing the unborn is patently absurd because, as noted by Josh Craddock in the Harvard Law Review:

[At] the time of the Fourteenth Amendment’s adoption, nearly every state had criminal legislation proscribing abortion, and most of these statutes were classified among “offenses against the person.” The original public meaning of the term “person” thus incontestably included prenatal life. Indeed, there can be no doubt whatsoever that the word “person” referred to the fetus. In twenty-three states and six territories, laws referred to the pre-born individual as a “child.'” Is it reasonable to presume that these legislatures would have used this terminology if they had not believed the fetus to be a person?

The Amendment says, “nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” [Emphasis added.] Thus, establishing the fetus as a person brings it under the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment. Even the Roe decision admits that.

But in 1973, the High Court went on to cite the hardships that might ensue if women were forced to carry their children to term, hardships that women have dealt with countless times:

Maternity, or additional offspring, may force upon the woman a distressful life and future. Psychological harm may be imminent. Mental and physical health may be taxed by child care. There is also the distress, for all concerned, associated with the unwanted child, and there is the problem of bringing a child into a family already unable, psychologically and otherwise, to care for it.… the additional difficulties and continuing stigma of unwed motherhood may be involved.

Who knew the process of making up laws could be this embarrassing?

The Court was willing to invent this entitlement out of thin air; but was not willing to allow for the possibility that an unborn child might be human—which most people recognize. When it came to the question of whether a fetus is a person, the Court felt it’s not specifically mentioned in the Constitution, so it doesn’t exist:

“No case could be cited that holds that a fetus is a person…In short, the unborn have never been recognized in the law as persons in the whole sense.”

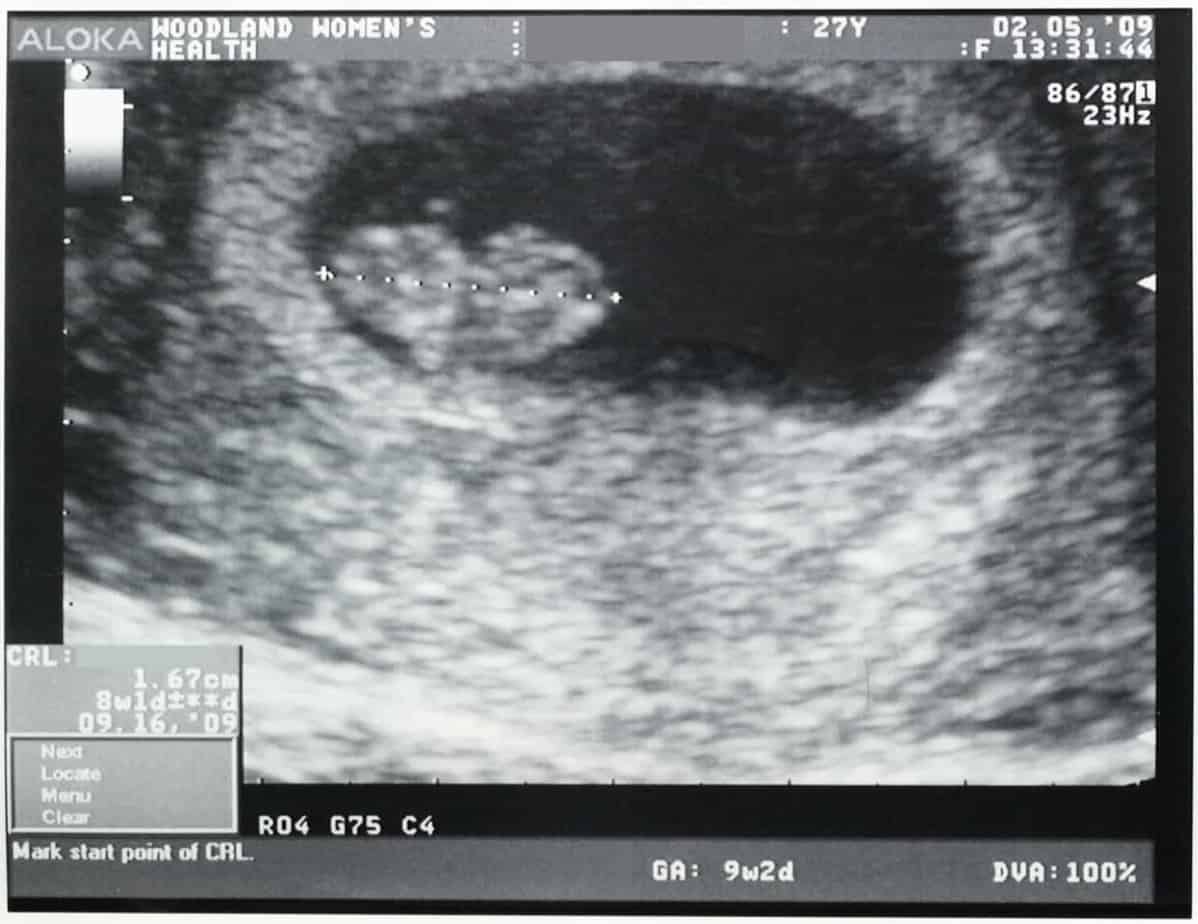

No case ever held that a woman had the right to kill her unborn child either; but the SCOTUS crafted a fictional right to allow, even encourage the latter. To support that contrarian view, the Court noted that in ancient Rome and Greece, abortion was not frowned upon. (Of course, the ancient Greeks didn’t have ultrasound.)

Science proves a fetus is fully human

The Law had never held that the fetus is a person, but science is the proper arena for investigating if fetuses are sentient beings, relying, not on the whims of judges, but “using the full range of empirical data available: experimental, clinical, and anecdotal (personal report).”

—David B. Chamberlain, a California psychologist, author, and editor who has lectured on birth psychology in 20 countries. He’s recognized as the premier investigator of the mind and emotions of the unborn child. Unfortunately, he passed away in 2014.

Is the unborn child part of the mother or a separate individual?

Science has determined that just before conception, the woman’s ovum contains 23 chromosomes—half the number held by a human being; these carry DNA from the mother. The sperm has 23 chromosomes also, carrying DNA from the father.

No matter what the courts have said, or failed to say, Science has proven that the instant conception occurs, a new person has been created, which then has the full 46 chromosomes. Its DNA is not the same as the mother’s—in even a single cell—thus it is a different person, not part of the mother, as claimed by the ignorant and the malevolent. Cutting it off like an unsightly mole is therefore murder.

Is the unborn child a sentient being?

Some of the following is excerpted from Chamberlain’s book, The Sentient Prenate: What Every Parent should know.

Human studies [show] that the prenate is intensely interactive (and vulnerable to) the whole fetal environment for better or for worse (Nijhuis, 1992; Roe & Drivas, 1993; Thoman, 1993; Ward, 1991). Especially impressive are the growing list of studies that demonstrate prenatal learning and memory for stories, music, voices, specific words and sentences, and particular languages (Busnel, Granier-Deferre & Lecanuet, 1992; Hepper, 1991; Thoman & Ingersoll, 1993).

Babies are sensitive and aware; they have definite preferences which they show by their spontaneous actions; when they are hurt, they feel pain; and when they are threatened, they react in self-defense. Memories of trauma are not forgotten; their influence continues unconsciously.

Do unborn babies feel pain?

Audible crying, the outward expression of pain, has been recorded by 21 weeks in cases of therapeutic abortion.

Alertness to danger and maneuvers of self-defense are illustrated by fetuses’ reactions to amniocentesis, a procedure usually performed between 9 and 16 weeks gestational age. Reactions noted have included the following: increase in heart rate, loss of beat-to-beat variations in heartbeat four minutes after puncture for two minutes, motionless for two minutes, breathing significantly slower for two days, and failure to normalize their breathing rate for four days. (Hill, Piatt & Manning, 1979; Manning, Piatt & Lemay 1977; Neldam & Pedersen, 1980; Ron & Polishuk, 1976).

While being viewed via ultrasound, a 24-week fetus who was accidently hit by a needle, twisted his body away, located the needle with its arm, and repeatedly struck the needle barrel (Birnholz, Stephens & Faria, 1978)! Similarly, in the midst of fetal surgery, an obstetrician reported that when he had a blood vessel all lined up and was ready to strike, a hand came out of nowhere and knocked the needle away (Baker, 1978).

One personal account is worth more than a dozen studies. Here are two; the first was reported by a researcher:

Spontaneous social communication has been observed between twin fetuses at 20 weeks (Piontelli, 1992). Using ultrasound, Alessandra Piontelli of Milan watched by the hour as Luka and Alice met and touched each other gently through the membrane which divided their space in the womb. The boy was very active and vigorous, the girl quite sleepy, but, periodically, he would come to the membrane and gently awaken her: she always responded. They would rub heads, play cheek to cheek, seemed to kiss and hug, stroked each other’s faces, and rubbed feet together until they returned to their solitary activities. This behavior was observed again and again over six hour-long observation periods until they were born.

Visiting them at home around their first birthday, the doctor found them taking great delight in playing together. Their favorite game was hiding on either side of a curtain, using it like the dividing membrane in the womb. Luka would put his hand through the curtain and Alice would reach out with her head as they began their mutual stroking, accompanied by gurgles and smiles.

Finally, there is this account showing that prenates are not only persons; they are aware of their surroundings and can remember them. The mother (and a prolific author), Melanie Jane Juneau explains:

Most of my nine children were able to verbalize their womb and birth experiences if my husband and I posed questions before they were three and a half or four years old because most children can no longer remember after that age.

The day my second child turned two, her godmother dropped by to celebrate her birthday. Since Jean was very articulate for her age, her godmother wanted to try an experiment she had read about in a hospital newsletter. The article stated that if you asked a young child when they knew enough words to communicate but before they were too old, they could tell you about their life in the womb. So we decided to test this premise.

Jean was tiny but smart, so she startled people with her clear diction and a large vocabulary. This particular day she was standing on a chair behind the kitchen table, playing with a new doll. During the conversation, she answered mainly with one-word sentences because most of her attention was on her toy.

I felt a bit foolish as I asked my daughter, “Jean, do you remember when you were in mummy’s tummy?”

She answered, “Yaa.”

So then I wondered if she remembered any details. “What was it like?”

Again Jean could only spare a one-word answer: “Warm.”

“What else was it like?” I questioned.

To which she answered quite succinctly, “Dark.”

“What could you see?” I probed.

Jean was frustrated by my dumb question. “Nothin’; it was dark!”

So I scrambled, “What did you do in my tummy?”

Jean said nonchalantly, “Dwimming.”

I checked to make sure I understood her. “Swimming?”

She nodded.

“Did you like living in my tummy?” I wondered.

She nodded again.

Then I thought of a really good question. “Do you remember coming out, being born?”

Jean scrunched up her nose and sighed, “Yaa.”

“What was it like?”

My toddler stopped playing, looked up and said in disgust, “Like a B.M. [bowel movement]!”

That answer shocked me into silence. I looked over at my sister-in-law.

She raised her eyebrows and said one word. “Wow.”

[Used with permission from Melanie Jane Juneau] Read it all here:

http://www.catholicstand.com/prenatal-memories-ancient-hebrew-wisdom/

Melanie Jean Juneau is the Editor in Chief at Catholic Stand. Her writing is humorous and heart warming; thoughtful and thought-provoking. Part of her call and her witness is to write the truth about children, family, marriage and the sacredness of life. Melanie is the administrator of ACWB, a columnist at CatholicLane, CatholicStand, Catholic 365, author of Echoes of the Divine and Oopsy Daisy, and coauthor of Love Rebel: Reclaiming Motherhood

https://themotherofnine9.wordpress.com