by David Reavill

I have the dubious distinction of being among the hundreds of thousands who lived through the Northridge Earthquake nearly 30 years ago. I grew up in Southern California and was used to large Earthquakes, but this one was special. Not only did the initial jolt seem of greater magnitude than all the rest, but what seemed especially memorable was the aftershocks, those repeated bumps after the initial quake.

Adding to the drama, I remembered that geologists tell us there is no way to know whether that first quake was “the big one” or merely a foreshock of an even larger quake.

So for the first couple of days after the quake, we sat out on our driveway, waiting for what would come next. We were without power or phones, so we were left to anticipate our future. As it turned out, there was no significant structural damage, and no one was hurt or injured.

Last week, you and I sat through another Earthquake that promised to be at least as severe as the Northridge Quake, but this wasn’t an actual quake; it was a financial Earthquake. And like back then, we will all sit out on the driveway, where it’s safe, hoping nothing worse comes along.

Just a week ago, on May 3, the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee adjourned their latest meeting and announced to the world that they were raising the Fed Funds rate to 5 1/4%, the highest rate since 2007. The feeling around here was, ho hum, another rate hike following a long line of hikes. Most people feel that “at least they didn’t hike rates anymore.”

Unfortunately, only some people understood the historical significance of what we’ve just witnessed. To use our Earthquake meme: what happened last Wednesday would register with the highest level ever recorded on the Richter scale, a 9.5.

Federal Funds are unique; they are the funds traded back and forth in the Banking System, providing overnight liquidity so that Banks can meet their “Reserve (Capital) Requirements.” It’s not unusual for a bank to fall out of “balance” without sufficient Reserve Capital to meet Regulatory Requirements.

A large unanticipated loan needs to be funded, a group of depositors decides to withdraw their funds, and a drop in collateral value can all cause the bank’s capital to fall under legal levels. The solution, take out an overnight Fed Funds draw. It provides the bank with sufficient reserves and is a quick, easy solution to a generally rare event.

Because Fed Funds are the shortest of all loans, they generally have the lowest interest rates. So Banks can hit the “Fed Window” without incurring an onerous expense.

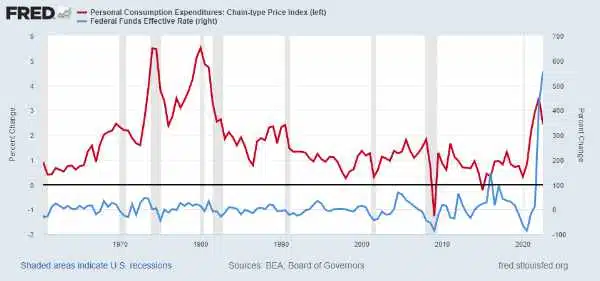

At this point, we see how very different today’s Federal Policy is than at any time in the last 60 years. (For today’s discussion, we will ignore Fed Fund’s spike that occurred in the year 1980 when Paul Volcker’s Fed first raised and then dropped the Fed Funds to tremendous highs and lows.)

So, except for the year 1980, the historical trend for pricing Federal Funds has consistently been below the inflation rate. In fact, except for a short blip in 2016, and that exception in 1980, the Fed has held the Fed Funds Rate Below 1%.

Put another way, the Fed has held the Fed Window wide open. They are allowing banks to cover any short-term losses quickly and inexpensively. It made the life of the Bank Financial Officer relatively easy. For instance, last year, if a Bank needed a billion dollars overnight, the interest cost was less than $7,000, which is very inexpensive. If that bank needs that same billion-dollar overnight loan tonight, the Fed Fund’s interest expense costs $143,000—quite a difference.

Suddenly the bank’s entire profitability changed. Whereas last year the bank might have funded a large loan right away, knowing that they could cover their requirements by using the Fed Window, now they may need to support your loan by other means like adjusting their deposit base. And loans that might have been funded in a day or two now could take much longer.

There is another thing to note on our Chart; in the upper right-hand corner, you’ll see that the Fed Funds Rate, currently 5 1/4%, is now higher than the Inflation rate. That’s the first time that’s happened in 60 years. This Fed has taken us into territory we have seen in all that time. Meaning that, for the first time, overnight Fed Funds will now be more expensive than the annual inflation rate. That’s about as restrictive as possible.

Typically economists consider a restrictive interest rate policy when a one or two-year interest rate is higher than the annual inflation rate. But today’s Fed is much more stringent than that. This Fed is applying the monetary brakes as hard as possible.

And what part of the economy will be hardest hit? That’s right; it’s the Banks; after all, they are the ones who use the Fed Funds Window.

We began this discussion talking about interest rates, but as you can see, most of the impact will be on Commercial Banks. We should call the current Fed Interest Rate Policy the Fed Bank Policy.

Commercial Banks’ entire cost structure is rising along with these higher interest rates. How can we expect the banks to react? They will likely respond as they always do in tough times. They will cut back on the number of loans offered. Lending standards will be raised, requiring better credit rating by the borrower and likely additional collateral. That credit card offers you get in the mail will probably stop. Existing loans will be scrutinized, and any late payments or lower credit scores will mean the bank will likely restrict your account. Some loans will be called, while others may require additional charges.

This Fed Action will significantly reduce business and personal loans. It will inevitably lead to a sharp economic slowdown as companies and individuals move to reduce their debt. We’ve already seen the first stages of this with the substantial number of layoffs.

The most likely scenario in this kind of credit tightening will be a general reduction in business activity. For many, it will be a financial earthquake.

A financial earthquake at the same as an earthquake of illegals invading the USA…

Ever since Biden became President there has been more and more trouble…

I apologize for being off topic but 3 people have been killed and there was some more shooting at the Pharr Reynosa bridge between Mexico and Texas.

Things are heating up…it seems…