YOU ARE WHAT YOU SPEAK: UKRAINE’S LANGUAGE PROBLEM

Gennady Shkliarevsky

The war in Ukraine has divided the world into two hostile camps. It undoubtedly poses the greatest danger ever to the survival of our global civilization. For many of us, both in the West and in the East, the war raises some heartrending issues: Is it really worth fighting? What is at stake in this war?

Among the many issues that divide the population of Ukraine and fuel the current conflict is language. Many citizens in eastern Ukraine, where most people speak Russian, complain that contrary to the promises that Mr. Zelensky made when he became president, his government today is trying to impose linguistic uniformity and force them to use Ukrainian.

The use of the Russian language is what the two breakaway regions in the east cite as a source of discontent among the people who live in these regions. The Ukrainian government denies the existence of any language problems. It claims that the continued festering of this issue is merely a result of Russian propaganda and interference as part of the efforts to end Ukraine’s independence, and the Russian language is one of the weapons of choice that Russia uses to achieve this goal.

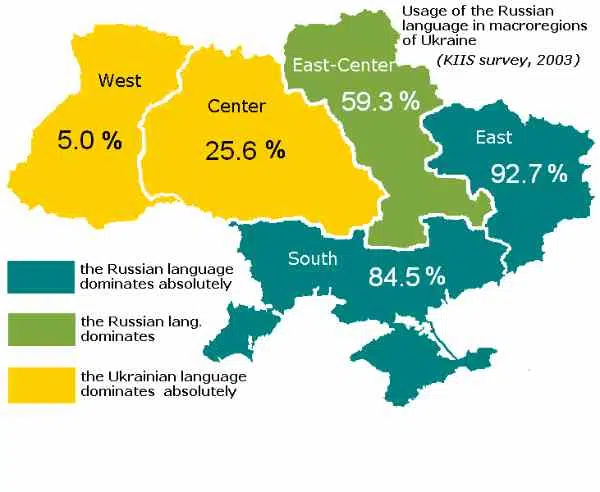

A little pre-history will provide the context. Ukraine has always been a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural country where the population has traditionally used many different languages. Russian and Ukrainian have been the two dominant ones. According to the poll conducted in 2013 by the independent International Institute of Sociology in Kiev, 56% of the respondents considered Ukrainian as their mother tongue, and 40% of the respondents named Russian as their native language.

There is also a territorial factor that plays a role: Russian is the language primarily used in the east of Ukraine where it has also always been used in an official capacity. Ukrainian was prevalent in the west of the country. The middle part of Ukraine, including the capital city of Kiev, has habitually used a mix of the two languages that is now called “surzhik”—a designation that carries a derogatory connotation.

The distribution in language use reflects a complex and often contradictory evolution of Ukraine, both as an area and a state. Until WWII, western Ukraine was not even part of Ukraine. Ethnic Russians played a very important role in the development of the eastern part of the country and its industrial potential that goes back to the 19th century. All these factors underlie the linguistic tensions that have become particularly acute since 2014.

The language problem emerged into the open when Victor Yanukovich, the erstwhile president of Ukraine, was overthrown in 2014. The overthrow prompted protests in east Ukraine that eventually led to the secession of the two regions in the east and the beginning of hostilities between the local population and the government in Kiev. Language has become one of the principal issues in the standoff between the government and its critics in the east and other parts of Ukraine.

Ukrainian nationalists often blame Russia for what they see as changing attitudes toward Russian in Ukraine. They claim that the war has had a powerful effect on the Ukrainian population, prompting people to demand the removal of Russian as a language of communication.

However, there is something that rings false about this claim. The assault on the Russian language started shortly after 2014, not after 2022, when the war began. Until 2014, the law of 2012 regulated the status of various languages in Ukraine. The basis for this law was the Constitution of Ukraine, which recognized Ukrainian as the state language but also guaranteed “free development, use, and constitutional protection” of Russian and other languages used by different ethnic groups in Ukraine.

In 2016 the Ukrainian legislature voted the law of 2012 unconstitutional. The Supreme Court of Ukraine took two years to consider this matter and eventually proclaimed the law of 2012 unconstitutional. Even before the recognition of unconstitutionality, the legislature began to adopt various legislative acts that limited the use of Russian in the media and education.

One of them is the law on education that severely limited the use of Russian in schools. In 2019, the national legislature adopted another law designed to ensure the exclusive use of the state language in many spheres and in everyday life, including media, commerce, and advertising. Many critics characterized this law as the beginning of the broad assault on the Russian language, or what was often called a “gentle Ukranianization” of Ukraine.

There is certainly more to be said about these legislative acts and their effects on the country. However, the purpose of this article is different. The interest that has inspired this article is more in the years after 2014 and the broad public discourse on language, culture, and values that have emerged during these years.

“Patriots” and president Zelensky claim that the current war with Russia is about Western values—the view that is widely publicized in Ukraine. My interest, though, is not so much in official stances and positions but more in the way that Western values and norms are understood and interpreted by ordinary Ukrainians. I have decided to use my contacts in Ukraine to learn more about the attitudes of ordinary Ukrainians—those that identify themselves as “patriots” and their opponents. This approach certainly has no pretensions of being comprehensive and exhaustive. All it tries to do is to give readers some idea about the complexity behind the current controversy over language and values in Ukraine.

A few days ago I posted in my feed a photo of an ad in one provincial American town. The ad said: “Never make fun of someone who speaks broken English. It means that they know another language.” In my neutral comments accompanying this post, I suggested that the view expressed in the ad might be a good point of departure for considering the language problem in Ukraine. I expected that this modest and neutral take would bring some well-measured observations largely devoid of emotional biases. The response was anything but. What follows are verbatim translations of some selected passages from that exchange (I use initials and not full names of respondents)

- R.: “We have no [language] problem. Ukraine is for the Ukrainian language. This is no problem for Ukrainians. It is only a problem for Putin’s propaganda that talks about ‘Ukrainians who speak Russian.’ How can this be in real life?”

- G.: “The official “approach toward minority languages is regulated by the Constitution and the Law on Language. Anything beyond that “what and how” is a personal matter of every individual.”

- R.: “We do not want to be like the U.S. where the language of invaders (English) replaced the language of native people . . . For us, Russians are invaders; they want to deprive us of everything Ukrainian–the language and culture in particular. Everything Russian, including the language, is alien to us.” (By the way, the author wrote this in perfect Russian.)

When I mentioned that many of my American FaceBook friends liked the poster and what it said, one respondent erupted into a diatribe:

- G.: “Tell your American followers that if they do not like our attitude [with regard to the Russian language], it is a problem of their lack of education . . . Those Ukrainian citizens who do not respect the state language of Ukraine and do not follow the laws are collaborators [with Russians] and are just disgusting imbeciles . . . You cannot compare Ukraine and the USA. America is a synthetic country where practically all citizens are immigrants from all over the world. Ukraine is a mono-ethnic country where 92% [of the people] consider themselves to be ethnic Ukrainians. Such comparison [between Ukraine and America] is a horrendous distortion.”

The latter respondent also expressed the view that ethnic Russians were “lazy, stupid, and not civically minded.” He confessed that for most of his life until 2014, he had spoken only Russian and then experienced a conversion in 2014. He saw no contradiction between the current language policies in Ukraine and the UN Charter for Human Rights (that he generally accepts but reveals little knowledge of details).

When I remarked in reference to his characterization of Americans who liked the ad as “ignorant” that these same Americans paid for the weapons that our government sent to Ukraine and, for this reason, deserve at least some respect and consideration, he quipped: “You can tell them that ignorant and, therefore, unfriendly to Ukraine, do not have to pay for these arms. Besides, these weapons are not free to us.” (I suspect that he did not mean all Americans, but only those, like me, who are not totally beholden to Ukrainian nationalists, but he did not elaborate.)

There was only one person among the respondents who opposed the prevailing view. He was evidently from eastern Ukraine. In his short remark, he insisted that there was a problem with language in his location and that he personally experienced many difficulties.

As a follow-up to this exchange, I have decided to interview one more individual on a separate occasion to get more sense of the situation. This individual is in his 40s. He was born in Sloviansk—a city in eastern Ukraine. He has a technical degree and is a business owner. The general tone of his responses was much less emotional. He was not angry and visibly tried to be fair. He lives in an area where over 90% of the population speaks Russian. All members of his family and his friends speak Russian. He was educated in Russian and conducts his business mostly among Russian speakers.

Interestingly, he mentioned in the interview that he had voted in favor of making Ukrainian the state language in the general referendum on the language. The reason? As he explained, the general consensus at the time of the referendum was that people would have equal access to both languages, even if one language would be formally recognized as the state language, which he thought was perfectly appropriate for Ukraine. In light of what he was saying, I asked him specifically how it was possible that 92% of Ukrainians in polls consider themselves ethnic Ukrainians. His explanation, based entirely on his personal experience, was that many people, including himself, did not differentiate between ethnicity and citizenship. Many people from his area thought that “native tongue” (or ridna mova) was Ukrainian because the courses on Ukrainian taught in schools were designated as classes in “ridna mova”—an explanation that I have found a bit confusing. His principal stance on the issue of language is simple: “you should understand both [languages] and speak the one you choose.”

He complained a great deal about the laws adopted since 2016. In his account, these laws severely restricted the use of the Russian language and disenfranchised Russian-speaking Ukrainians. According to these laws, all official government business should be conducted in Ukrainian at the center and local levels. All business documentation, communication, and advertising should also be in Ukrainian. Even when doing personal shopping, one is required to use only Ukrainian. Non-compliance incurs heavy fines. Repeated offenses can even result in prison terms of up to three years in jail.

For my interviewee, these laws create a lot of problems since he has to advertise to predominantly Russian speakers. Those who do not speak a current version of Ukrainian (that differs from the version spoken during Soviet times) cannot work in the government and the media; they cannot be elected, and also suffer from other disabilities. Education is another sphere where language laws have negatively affected people in the east. Students in colleges and universities often do not understand and adequately appropriate the material in classes conducted in Ukrainian.

I asked the interviewee about the response to these changes by the people from his area. He said that some, but very few adapted; others continued to suffer from disabilities. His own use of Ukrainian is limited, and he prefers to use Russian. Interestingly, he puts much to blame for the raging language controversy on the so-called “patriots.” He blames them even more than he blames the government.

“Patriots,” as he explained, are the principal enforcers of the laws on language. The adoption of these laws has encouraged telltale and snitching. According to the interviewee, there is a great deal of “patriotic” vigilantism going around. He also thinks that Russian special agencies are likely to be behind this vigilantism as a way to create divisions and sow discord among Ukrainians.

An exhaustive examination of this vast and complicated topic is certainly beyond the scope of a popular piece. Researchers will eventually provide a full picture of how this controversy emerged and evolved.

In the meantime, however, it continues, thus undermining the unity of Ukraine. Ironically, as my interviewee has pointed out, changes are not particularly good for the use of the Ukrainian language. As a language of communication, it has limitations. Many citizens in the east and elsewhere in Ukraine try to learn another language or two (for example, English, German, or Polish) that would give them and their work broader exposure—something Ukrainian does not do. All in all, the controversy over language appears, at least to this observer, to be totally counterproductive in both the short and long run. It is divisive, confusing, and ultimately has little relevance to the country’s real needs and its people. Moreover, it generates attitudes that contradict precisely those Western values for which many Ukrainians claim they are fighting in this war.

~~~

Dr. Gennady Shkliarevsky is Professor Emeritus of History at Bard College.

Zelensky’s history of ethnic race cleansing in cooperation with KKKJoe Biden and George Soros, two of some of the mega-racists and segregationists in history spells it all out.

The good professor has validated my often repeated point, which is the USA and Europe has no interest in interfering with a conflict between two Rus tribes that has been raging for centuries. Have we not learned our lesson when we became involved in the millennial conflict between the Shiites and Sunni? We waste our resources badly required at home… Read more »

I cannot agree with you more.

We are in Ukraine because it was a Failed State that was the Clearing House and Money Laundry for the Ultra-Rich members of the World Economic Forum and Nation States. The corruption that was flowing through Ukraine was in the Billions, possibly Trillions of Dollars. We are in Ukraine to protect the WEF’s Sodom and Gomorrah. If you review the… Read more »

The language itself was a means to an end. The followers of Stepan Bandera saw themselves as fighters against the Soviets in WWII. As such, they maintained the anti-Soviet ideology, which then became synonymous with “Russians“. These small groups gained momentum after the 2014 Maidan coup, led by Nuland and Pyatt, which elevated the Banderites and their Nazi ideology. (For… Read more »

Again, I have to say that you follow the developments pretty well.